Potential causes of differential outcomes by ethnicity in legal professional assessments

3 June 2024

Research summary

Background

There is a widely acknowledged and long-standing difference in legal qualification outcomes by ethnicity. Our annual education and training monitoring reports show this difference and it is also evident in other sectors, countries and stages of education.

To investigate this further, we commissioned the University of Exeter to:

- look at what causes these different outcomes

- increase our understanding about the factors that are driving these differences

- identify ways to help to improve outcomes for all students.

The legal assessments considered in this research were those that pre-date the Solicitors Qualifying Examination (SQE), such as the Legal Practice Course (LPC) and the Graduate Diploma in Law (GDL).

However, not unexpectedly, we are also seeing a difference in outcomes in the SQE, and we are monitoring this by diversity characteristics. Our quality assurance processes include reviewing how we make sure that the examination itself is fair and free from bias, and we have a detailed evaluation programme for the SQE. We will take on board the findings from this research as we continue with our evaluation programme.

The research

The interdisciplinary study was carried out by the University of Exeter, with academics from law, business and psychology. The research team used a wide range of methods to maximise the validity and robustness of the findings, including:

- A thorough literature review, which was published in June 2023. This identified some gaps in past research and informed the rest of the project, which importantly captured the experiences of those most affected.

- More than 1,200 survey responses from law degree and LPC students.

- 59 interviews with:

- law students and recently qualified solicitors

- educators teaching law degrees and professional qualifications

- those holding senior positions in law firms, or working with law firms, most of whom were solicitors.

- Analysis of data on education outcomes:

- at different stages of schooling into university

- in other professions.

- Engagement with an external reference group with a broad range of expertise, including voices of those with lived experience.

Key findings

This is a complex issue and, as expected, the research team did not find a simple or single cause or solution to the issue. Most past research focused only on one aspect of the potential causes but we were determined to explore all the relevant factors and understand how they overlapped and affected candidates through their legal education and journey into the profession.

The findings have confirmed the complexity and breadth of the potential causes that were identified through the literature review. The research also provides evidence of how potential causes combine to impact education outcomes (including in legal professional assessments).

The research report highlights a wide range of possible ways to address the differential outcomes for minority ethnic students. Including many ongoing initiatives that we and others can learn from.

An overview of the findings by theme are set out below.

Social and economic background

- Students' socioeconomic background affects their early education options and experiences. Those who achieved better education outcomes tended to be from families with the financial resources and time to support their studies as well as knowledge of the education system and professional requirements.

- The literature review found that being part of a minority group increased the likelihood of experiencing discrimination and bias. This research then found that minority ethnic students have often experienced racism and teachers' low expectations of their capabilities. These students had developed coping strategies to deal with this, which can take energy away from studying.

- These experiences and resources impact students' confidence, self-esteem and exam preparedness, eg respondents from independent schools had higher confidence and more opportunities to practise exam skills.

School and university outcomes

- The Department for Education's data show that differential education outcomes can be seen early, particularly for Black pupils taking A-levels.

- These patterns can also be seen for all minority ethnic groups at university with 60% of Black students and 70% of Asian students achieving a first or upper second-class (2.1) degree, compared to 79% of White students.

- This research found that those who achieved better professional education outcomes tended to have fewer challenges in education before university. Such experiences were influenced by factors including location, peers and the support received from teachers.

Fitting in and support

- Students' confidence, the support they receive and how much they feel that they belong or fit has a significant effect on their outcomes.

- Lack of representation and diversity of staff and curriculum in legal education can impact students' feeling of belonging and/or that they 'fit' within law.

- It can also lead to microaggressions and bias in the classroom from academic staff, impacting minority ethnic students' learning.

- The interviews showed that the large student numbers in many law schools impacts how well educators know their students and their names, and their capacity to provide support where needed.

Access to legal work experience

- Having legal work or training opportunities, and/or paid education sponsorship, eases students' financial pressures and provides a support network and networking opportunities. All of these were found to benefit students' confidence and self-belief which, in turn, impacts their outcomes.

- The research showed that while 24% of Asian and 26% of Black LPC students' employers paid for their course, it was 45% for White LPC students. The interviews found that getting legal work or paid training is currently an easier process for those already with contacts in the profession.

- Recruitment processes that rely on A-level results, without looking at the context in which students received those grades (such as the school attended and their personal circumstances), were more likely to lead to White students being recruited. This was evident in the literature review and interviews and was found to perpetuate the status quo of diversity and representation in the profession and in education outcomes.

- The research showed 43% of Asian and 45% of Black LPC students had a legal role secured for when they completed their LPC, compared with 66% of White students.

Collective responsibility

- Collaborative action is needed to address differential outcomes.

- Law firms, education providers, representative groups and individual academics are implementing individual initiatives that are helping small numbers of students. However, the impact is limited because all are working at small-scale and/or in isolation.

- Some initiatives working well include making classroom environments more inclusive, having more professional role models, using contextual recruitment and having alternative routes through legal education and for work experiences, such as apprenticeships.

Suggested actions and discussion points

Collaboration is a key element in improving future education outcomes, as the complexity of the causes cannot be remedied by one set of actions or one set of stakeholders. The actions noted in the report are therefore a useful set of discussion points for stakeholders to consider when deciding what they should do.

These actions focus on areas where there is the potential to improve factors such as representation, feelings of fit and belonging, and the support available to minority ethnic students and exam candidates.

When deciding what to do, it is important to:

- avoid blanket assumptions about minority ethnic individuals and their circumstances

- consider the specific needs of the groups or individuals being supported and empowered.

As highlighted in the report, some existing initiatives implemented by the stakeholder groups are already taking forward many of these ideas. We can all learn from the experiences of those who delivered and/or participated in these initiatives.

The research also provided recommendations for specific groups or organisations:

Legal education providers

Providers can learn from their own and/or others' existing actions and go further to:

- Increase understanding of the need and ways to support minority ethnic students.

- Ensure greater diversity among teaching staff, senior leadership and decision-makers.

- Ensure that senior management at educational institutions take responsibility for reducing differential outcomes.

- Provide more resources for practical help to increase academic skills, such as assessment preparation.

- Enable greater collaboration with law firms for paid work experience opportunities, practical help with lawyer skills, including soft skills, networking, and cultural capital.

Law firms

Firms can learn from their own and/or others' existing actions and go further to:

- Have safe spaces and inclusive cultures for all staff and trainees.

- Use contextual recruitment, especially for roles involving funded preparatory courses for legal professional assessments.

- Measure recruitment and retention performance against appropriate diversity targets for all levels.

- Provide focused mentorship and sponsorship to minority ethnic staff and trainees.

The SRA

The SRA can continue and expand activity in:

- Playing a leading role as a change agent in progressing diversity across the profession, eg showcasing good practice and convening stakeholders.

- Monitoring diversity data and initiatives across the profession and education.

- Sharing relevant diversity research with stakeholders to support evidence-based practice.

- Providing information about qualifying as a solicitor.

- Increasing the SRA's ethnic diversity at leadership levels.

The sector

Overall, we can all consider whether and how to:

- Improve regulation of professional legal education: ie by changing the regulatory remits so that there is more scope for the SRA's involvement in educational matters.

- Improve access to and quality of legal career advice, including on the accessibility of legal careers – eg multiple routes into the profession.

- Regular reviews of policies and practices.

Next steps

We will develop and finalise a collaborative action plan that is informed by the research findings and by working with others across the sector.

We will also invite people and organisations to reflect on and share views on the research before agreeing a collective way forward. To achieve this, we plan to bring together law firms, education providers and representative groups later this year to agree how we can work together to address the issues identified in the report.

We note the importance of representation, assessment preparation and the value of paid work experience and networking opportunities. Therefore, our action plan will likely include updating and more widely publicising our:

- law firm diversity data tool, so that the current diversity of the profession is more visible to those in education and the profession

- information about qualifying as a solicitor

- apprenticeship information for aspiring solicitors and employers

- SQE assessment information which includes the assessment specification and sample questions for both SQE1 and SQE2. Along with information on what to expect on the assessment days and how to get a range of help and support.

Our Corporate Strategy for 2023-26 highlights that one of our aims for the SQE is to open up access to the profession to aspiring solicitors from every background. Findings from this will help inform our SQE evaluation programme, phase three of which is starting this year.

We publish the SQE results data. In due course, our SQE data collection (and publication) will allow us and others to examine a larger body of data, across a single assessment that is centrally marked. Over time, this will allow us to develop a more nuanced understanding about the results by various diversity characteristics.

And we will progress our action plan to significantly improve ethnic diversity at senior levels in the SRA.

Full research report and findings (University of Exeter)

Professor Greta Bosch (University of Exeter), Professor Ruth Sealy (University of Exeter), Professor Konstantinos Alexandris Polomarkakis (Royal Holloway University of London), Dr Damilola Makanju (University of Exeter), and Associate Professor Rebecca Helm (University of Exeter Evidence-Based Justice Lab)

With the research assistance of Dr Christopher Begeny and Mr Christopher Brown

This is the final report of the research commissioned by the Solicitors Regulation Authority (SRA) to better understand the reasons behind differential outcomes by ethnicity in legal professional assessments.

The SRA's annual education and training monitoring reports show persistent differences in outcomes in the Legal Practice Course (LPC) and Common Professional Examination (also known as the Graduate Diploma in Law) qualification routes for solicitors. The difference is also evident in the new Solicitors Qualifying Examination (SQE) data.

Differential outcomes by ethnicity are a long-standing problem, affecting all levels of education and a range of professional assessments, not limited to the legal sector.

Aims and objectives

The overarching research question that the whole project sought to address was: 'What are the potential causes of differential outcomes in legal professional assessments?'

More specifically, the project sought to:

- investigate key factors that could explain why differential outcomes exist across ethnic groups;

- establish the nature of the relationship(s) among these factors;

- distinguish, to the extent that this was possible, those that are of a more general educational nature, from those that may be unique to the legal context.

Research approach and methods

This is the final report of the project. It consolidates the findings of two years of research, including:

- systematic literature review (SLR): Desk research on what prior academic studies tell us about the issue, with a starting pool of 6,285 academic journal articles written since 2010. This review forms the backbone of the Workstream 1 report;

- comparative sector data: Looking at publicly available data and publications considering other professional assessments and levels of education, to further contextualise differential outcomes in legal professional assessments;

- new quantitative data: Survey data on aspiring solicitors at undergraduate (UG) and legal professional qualifications levels (UG students and LPC Candidates). These data form the backbone of the Workstream 2 report on Quantitative Data Insights;

- new qualitative data: Interviews to understand the experiences and attitudes of legal educators (Educators), senior individuals within or working with law firms (Seniors), and minority ethnic candidates, aspiring to take or who recently had taken legal qualification exams (Candidates). These data form the backbone of the Workstream 2 report on Quantitative Data Insights.

Some participants mentioned the SQE in interviews. However, since a separate, independent and in-depth evaluation of the SQE will be commissioned by the SRA, findings and actions relating to the SQE specifically were outside the remit of this commissioned research. An independent evaluation of the SQE is being commissioned this year and likely to be published next year, for phase three of the the SRA's evaluation framework.

Findings

The cumulative findings of the research are grouped under four key causal explanations underlying differential outcomes by ethnicity, which we elaborate below. The first three represent clear time periods or contexts relevant to our research question:

- Background (including family and pre-school to pre-university education).

- Legal education (including UG, postgraduate (PG), and professional qualifications).

- Legal profession.

And we found a fourth explanation, which did not relate to a particular time period:

- Overarching factors (including confidence, sense of belonging and self-efficacy).

Looking at recent official data, fewer differences in outcomes by ethnicity were observed in early years of education. These became more pronounced at A-levels and even more so beyond that.

The research noted that the patterns of differential outcomes in professional assessments in medicine and law were similar. It also noted the scarcity of data on differential outcomes by ethnicity in relation to assessments for other professions.

Overall, even though differential outcomes can generally be attributed to more cross-cutting factors, such as education and background context, there are factors specific to the legal context that play an important role alongside those. Some of these specific factors are:

- the lack of representation of minority ethnic solicitors in parts of the sector, especially in senior roles;

- the increased difficulties of getting funded support for legal professional education and/or assessments from law firms for future candidates from some backgrounds.

It is also important to note that various strands of research for this project brought up issues associated with terminology and categorisation. Grouping data on minority ethnic groups together, sometimes arbitrarily, can obscure nuances for certain minority ethnic groups, preventing the identification of important factors specific to them. Categorisation issues also feed into the available data.

Although available data are better than for some other professions, some interviewees called for more detailed data and further data disaggregation in relation to legal professional assessments.

Limitations

As with much research, the original data generated through our research had limitations that should be considered in interpreting the data. Full considerations are included in the Qualitative Interview and Quantitative Data Insights Reports respectively.

One important limitation to note is that the participants in our research are not necessarily representative of all participants who sit the LPC. Our sample did not have proper representation of participants who were relatively low achieving on the LPC. Moreover, we did not interview any candidates who had failed the LPC.

There were also limitations from the relatively small sample size in our surveys, compared to the overall numbers in UG and professional legal courses. This means that our raw findings should be read in conjunction with the available figures for the performance of the totality of the student population.

We attempted to confront issues around categorisation in our surveys by collecting information on participants' ethnicity, which resulted in having up to 20 different ethnicities in the data. However, due to the low sample size of the survey data, for analysis the participants had to be grouped under broader categories, which we acknowledge may mask important differences.

Background context

Background context refers both to environmental circumstances and education prior to university.

Environmental circumstances, such as socioeconomic status (SES) and family context were identified in the SLR and in our interviews as causal factors of differential outcomes. They also exemplify the intersectional character of the issue (intersectionality, as defined in the report for Workstream 1, is concurrently holding multiple and overlapping marginalised identities, and the implications that flow from that). Minority ethnic interviewed Candidates experienced ethnicity-based differences early on in their lives, regarding their education and other related factors.

Our survey also highlighted some potential differences in environmental circumstances based on ethnicity, eg minority ethnic participants were more likely to have received free school meals than their white peers. However, it should be noted that these differences were not consistent between different ethnic groups.

Moreover, several other differences expected on the basis of prior research were not found in our sample. This could potentially be attributed to self-selection bias among the survey respondents, resulting in an unrepresentative sample.

Prior education experience was also identified in the SLR as an important standalone influential factor to differential outcomes. The characteristics of the school someone attended, and their pre-university experience affect a range of aspects: skills, social and cultural capital (ie having the knowledge, skills and ideas that are valued in a group or society), confidence and motivation.

These aspects intersect with, and impact, the overarching factors that may explain differential outcomes, such as someone's self-esteem and remaining persistence. We define the concept of 'remaining persistence' as a person's willingness to keep pursuing or persisting in actions to achieve a specific goal in legal education and profession (referred to simply as 'persistence' in socio-cognitive career theory (SCCT); Brown and Lent, 2019). That is, prior experiences can impact someone's reserves to keep pursuing their education and professional goals.

Importantly, our survey data showed differential outcomes between different ethnic groups (with white students demonstrating the best outcomes) in our sample even at General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) level.

Interviewees touched on the lasting impact of negative early education experiences in later stages of their education and career. And we can see this impact in our online surveys which showed lower levels of:

- a sense of belonging and positive relationships, for Mixed ethnicity, Asian, and Black Candidates;

- academic press, referring to ''normative emphasis on academic success and conformity to specific standards of achievement'' (Lee & Smith, 1999), for Black Candidates;

- academic motivation, referring to 'students' general interest, engagement, and enjoyment in learning and school' (Anderson-Butcher et al., 2012, p. 187), for Asian and Black Candidates

than their white peers in early education (ie their education prior to university).

It is worth noting that this study identifies lower levels of the above factors among specific ethnicities (as indicated above). But this does not imply that these factors are inherent in certain ethnicities. Instead, as we go on to show, the challenges that some people experience, often because of their ethnicity, cause differences in levels.

Legal education context

A range of potentially influential factors for differential outcomes arise in the context of legal education:

- Lack of tailored support as an outcome of the huge expansion of student numbers in law degrees (the 'massification' of legal education). This was viewed as an obstacle to addressing any disparities that exist because of the background context. Addressing disparities early on in a degree is crucial, as this period can prove influential for skill development and success in law firm recruitment.

-

Financial constraints were identified in both the surveys and interviews as an ongoing concern for candidates, especially given the high costs of training for and sitting or resitting legal professional assessments. Having to take up non-legal but paid employment takes time away from studying. Moreover, worries about money while not having a funded LPC can influence self-esteem, outcome expectations, and remaining persistence, in turn potentially impacting outcomes.

To put this in context, our survey showed that, compared to white Candidates, Asian and Black Candidates were less likely to obtain sponsorship from an employer on the LPC. Moreover, Black Candidates were the most likely to have family or friends financially supporting their LPC, while Asian Candidates were the most likely to self-fund.

- Lack of representation and diversity of staff and curriculum in legal education can impact students' feeling of belonging and/or that they 'fit' within law. It can also lead to microaggressions and bias in the classroom from academic staff, impacting minority ethnic students' learning. Microaggressions are also present in interactions between students, feeding into overarching factors of exclusion, belonging and remaining persistence. Asian, Black, and Mixed ethnicity participants in our LPC and UG surveys, reported higher levels of discrimination and lower levels of representation, and that the curriculum does not match their realities and/or experiences ('curriculum fit'), compared with white Candidates.

These factors often cut across UG and PG/professional legal education. They also intersect with factors that tend to arise earlier in one's life/education cycle. For example, Advanced level qualifications' (A-levels) performance (a factor related to background context) is important for entry to university, but also for accessing law firm schemes that cover preparatory courses and maintenance.

Legal profession context

The legal profession can also impact on differential outcomes in various ways, despite no obvious direct influence on legal education and assessment and despite being at the end of several years of potentially negative influences on minority ethnic individuals.

The lack of representation and diversity in the senior levels of the profession, in particular in the larger firms, together with perceptions of elitism and inaccessibility, can negatively influence minority ethnic students' and candidates' belief that they could succeed or simply 'fit' in with the legal profession. Indeed, our survey data confirmed lower ratings of representation of people 'like them' in the legal profession and lower ratings of identification with the legal profession for Asian, Black, and Mixed ethnicity Candidates.

Hiring practices based on restrictive definitions of merit can accentuate the impact of differential outcomes in later stages of one's life, beyond influencing candidates' beliefs about their potential. For example, A-Level results influence recruitment for training contract opportunities that cover preparatory courses for legal professional assessments (eg LPC sponsorship).

The lack of universal financial support during the preparatory stage for legal professional assessments may influence outcomes. Our interviewees noted this could especially affect outcomes for those from 'nontraditional backgrounds', ie those that tend to be underrepresented in the law firms that provide such support. From our survey sample, Asian, Black, and Mixed ethnicity Candidates were less likely to have legal employment lined up for when they completed their LPC compared to their white peers, a factor that may also impact their motivation for doing well in legal professional assessments.

Overarching factors

The preceding contexts are key for better understanding and locating some potentially multilevel causal explanations for differential outcomes. At the same time, a series of causal factors, which cut across these contexts, can also be identified (such as lower sense of belonging, reduced confidence and remaining persistence, etc). For example, minority ethnic individuals educated in the UK might have experienced years of microaggressions, lowered expectations and alienation, resulting in a lower sense of belonging. The latter is exacerbated by a lack of representation, diversity and role models in both legal education and the profession.

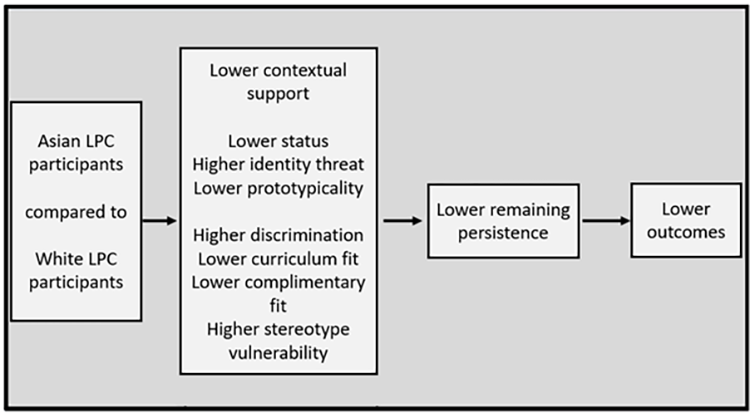

The negative experiences all create a sense of doubt in the students' or candidates' perceptions of their own capabilities, which can cause a reduction in their confidence and ambition as seen in the interviews. In addition, when comparing Asian to white LPC Candidates, the survey data reveal that lower levels of remaining persistence partly explain lower academic outcomes, and specifically explain the relationships between the following factors and lower outcomes:

- a more adverse background context (in terms of lower contextual support);

- less favourable perception of how they see themselves in the legal profession (in terms of lower perceived status, not feeling like a typical solicitor (lower prototypicality) and a feeling that others perceive that the competence of people with their identity is lower (higher identity threat);

- more negative social interactions in legal education (in terms of lower curriculum fit, not 'fitting in' with their academic life (lower complementary fit) in law school, and higher discrimination and vulnerability to stereotypes).

These negative experiences do not necessarily stop students or candidates from pursuing legal education or from trying to qualify, but certainly create additional hurdles throughout this journey. As such, they partly explain some differential outcomes. It is worth clarifying that while this study may identify lower levels of remaining persistence among specific ethnicities, it does not imply that ethnicity is a determinant of persistence.

Experiences of initiatives to address the differential outcomes

The interviews revealed some successful initiatives that our interviewees suggested contributed to addressing differential outcomes. Quite a few of these referred to types of initiatives identified in the SLR and in our comparative research but applied to and discussed in the legal context. The initiatives can be categorised as:

- Initiatives to increase accessibility and aspirations: outreach schemes and paid work experience.

- Initiatives aimed at individual support for students, at the start and throughout their higher education journey and into legal qualifications.

- Initiatives to address affirming cultures in Higher Education (HE): inclusive classrooms and professional role models.

- Initiatives regarding inclusive curriculum and diverse assessments.

- Recruitment initiatives, including contextual recruitment, use of targets and alternative routes such as solicitor apprenticeships.

- Data-driven initiatives at the firm level to improve recruitment, retention and inclusivity.

Expert-suggested actions

This two-year project aimed to identify some of the underlying causes for differential outcomes on the basis of ethnicity in legal professional assessments. Based on the information gathered and analysis conducted, we have identified some challenges faced by many minority ethnic students and candidates.

Reflecting on the findings of the whole project, and drawing on our expertise, we identified a series of potential actionable insights for the key stakeholders involved most closely with legal professional assessments. These stakeholders include:

- those with responsibility for the provision and delivery of legal education at all levels;

- law firms;

- the SRA as the regulator of solicitors in England and Wales.

The suggested actionable insights have the potential to improve factors such as representation, feelings of fit and the support available to minority ethnic students and candidates.

Some causes and challenges will be easier to fix than others, and the research has not identified neat solutions. Instead, we have grouped together ideas for key stakeholders to consider. We acknowledge that some existing initiatives implemented by the stakeholder groups are already taking forward these ideas. The main report highlights many of these existing initiatives and discusses the benefits seen from these in addressing differential outcomes, along with the specifics about how the potential actions could be implemented.

More generally, it is important to reiterate that being nuanced about the specifics of the groups or individuals being researched and/or supported is essential, in order to avoid blanket assumptions about minority ethnic individuals and their circumstances.

For those with responsibility for the provision and delivery of legal education

Consider how all providers can learn from their own and/or others' existing actions and go further to:

- Increase understanding of the need and ways to support minority ethnic students.

- Ensure greater diversity among teaching staff, senior leadership and decision-makers.

- Ensure that senior management at educational institutions take responsibility for reducing differential outcomes.

- Provide more resources for practical help to increase academic skills, such as assessment preparation.

- Enable greater collaboration with law firms for paid work experience opportunities, practical help with lawyer skills, including soft skills, networking, and cultural capital.

For law firms

Consider how all firms can learn from their own and/or others' existing actions and go further to:

- Have safe spaces and inclusive cultures for all staff and trainees.

- Use contextual recruitment, especially for roles involving funded preparatory courses for legal professional assessments.

- Measure recruitment and retention performance against appropriate diversity targets for all levels.

- Provide focused mentorship and sponsorship to minority ethnic staff and trainees.

For the SRA

Consider continuing and expanding activity in:

- Playing a leading role as a change agent in progressing diversity across the profession, eg showcasing good practice and convening stakeholders.

- Monitoring diversity data and initiatives across the profession and education.

- Sharing relevant diversity research with stakeholders to support evidence-based practice.

- Providing information about qualifying as a solicitor.

- Increasing the SRA's ethnic diversity at leadership levels.

For the sector

Consider whether and how to:

- Improve regulation of professional legal education: ie by changing the regulatory remits so that there is more scope for the SRA's involvement in educational matters.

- Improve access to and quality of legal career advice, including on the accessibility of legal careers – eg multiple routes into the profession.

- Regular reviews of policies and practices.

The annual education and training monitoring reports of the Solicitors Regulation Authority (SRA) show the existence of differential outcomes across ethnic groups in the legal professional assessments to qualify as solicitor in England and Wales.

Data drawn from the Legal Practice Course (LPC) and Common Professional Examination (also known as the Graduate Diploma in Law), the mainstream routes to qualification before the introduction of the Solicitors Qualifying Examination (SQE), confirm that the issue has been long-standing. They also show differences across all types of outcomes (grade band awarded, pass rates and the proportion of students that defer (delay starting or progressing with a course), or are referred (where students can retake the assessment because they did not pass)).

Early indications from the SQE confirm the existence of differential outcomes on the basis of ethnicity in the new assessment also, which form part of the SRA’s evaluation of the SQE. Such differential outcomes, therefore, seem to be long-standing and persistent.

The differential outcomes for LPC results are also discrete among different ethnic groups, as shown in Figure 1. For example, white students are more likely to have a distinction (the highest grade) result; Asian and Black students are more likely to have a referred result (did not pass but can retake the assessment); and Black and Mixed ethnicity students are more likely to have withdrawn (stop taking the course).

Figure 1: 2020/21 LPC results by ethnicity

n = 15,037

Source: SRA, 2022, Education and training authorisation and monitoring activity September 2020 - August 2021

While disappointing, the issue of differential outcomes is not unique to legal professional assessments for solicitors' qualification. The Bar Standards Board (BSB) published in 2022 a research report on differential outcomes on the Bar Professional Training Course. Other professions, like medicine, have also undertaken research to trace and better understand the differential outcomes evident in their respective professional assessments. These build on a rich body of data and literature describing differential outcomes by ethnicity across the different levels of education, from pre-school to university. Differential outcomes exist across the education journey and into professional assessments.

There have been numerous discussions of differential outcomes by ethnicity at school and/or university level. However, there has been less interest in the context of professional assessments (at least in the UK), except for the medical profession.

In addition, despite research on the causes of differential outcomes in education, differential outcomes by ethnicity have only slightly improved over time for the most part. Moreover, in certain professional assessments outside the legal and medical sectors, there is a shortage of publicly available data to even check whether differential outcomes exist.

Finally, even though there are data that show the extent of differential outcomes in legal professional assessments, at the moment there is not a developed body of research around the key factors that explain such outcomes.

Research aims

Against this backdrop, the SRA commissioned this research. The overarching research question for the whole project was: What are the potential causes of differential outcomes in legal professional assessments?

More specifically, the project sought to:

- investigate key factors that could explain why differential outcomes exist across ethnic groups;

- establish the nature of the relationship(s) among these factors;

- identify, to the extent that this was possible, those that are of a more general educational nature, from those that may be unique to the legal context.

Research methods

Varied methods were used to answer the research questions across two workstreams:

- Systematic literature review (SLR): Desk research on what prior academic studies tell us about the issue, with a starting pool of 6,285 academic journal articles written since 2010 (forming the backbone of the Workstream 1 report).

The second workstream consisted of:

- Comparative sector data: Comparative data research by looking at publicly available data and publications, considering other professional assessments and levels of education, to further contextualise differential outcomes in legal professional assessments.

- New quantitative data: Collecting survey data on aspiring solicitors at undergraduate (UG), postgraduate (PG), and professional legal qualifications levels (LPC Candidates) (for further detail, see Quantitative Data Insights Report). While the LPC is a PG-level course, our other PG sample included students on other PG law courses and past LPC students. However, this PG sample size was too small to conduct a full analysis, so we focus our reporting on the UG and LPC samples.

- New qualitative data: Interviews to understand the experiences and attitudes of legal educators, senior individuals within and working with law firms, and minority ethnic candidates (for further detail, see Qualitative Interview Insights Report).

Across the four sources of data considered in this final report there were three clear time periods or contexts relevant to our research question, which initially became evident during the SLR stage:

- Background (including early and pre-university education);

- Legal education (including UG, PG, and professional qualifications);

- The legal profession.

In addition, each also had some overarching factors that could explain differential outcomes.

The data sources each use different language and terminologies. The language in the interview data comes from 'invivo', meaning from words the interviewees used. While the language from the survey data generally comes from previously used verified academic scales and measures.

When describing and analysing each source of data we defer to the language used in the data. Therefore, to aid the reader, below, we list these to show how they overlap.

1. Background context (including early and pre-university education)

The SLR and comparative data refer to research and data on preschool and school education.

The interviews consider schooling, socioeconomic status (SES), and broadly family background.

The survey data refer to prior attainment (GCSE, A-Levels), early education, type of secondary school, and SES.

They all also consider broader background contexts such as level of English, financial and familial support and knowledge of the profession.

2. Legal education context (including undergraduate, postgraduate, and professional qualifications)

The SLR and comparative data discuss college (particularly US studies), university and law school (meaning PG level in US studies), and legal qualifications.

The interview data covering this period include:

- the transition to the university environment, including any induction;

- the impact of personal finances;

- the 'massification of higher education' (referring to the huge expansion of student numbers in law degrees) and institutional constraints caused by this;

- staff-student interactions and expectations;

- the lack of representation or diverse staff and the impact this has on teaching;

- and the curriculum and forms of assessment at UG and PG levels.

The survey data refer to:

- learning experiences;

- social interaction;

- academic aspects of law identity;

- and funding sources (eg of the LPC courses).

3. Legal profession context

The SLR and comparative data describe professional and employment contexts.

The interviews focus on perceptions of:

- organisational inaccessibility and the lack of representation;

- the role of training contracts;

- hiring practices.

The survey data focus on professional aspects of law identity (ie the extent to which students see themselves as potential members of the legal profession) and future employment.

4. Overarching factors

One of the issues associated with much of the academic literature reviewed in the SLR was that it focused on single factors, often only at the individual level. This is problematic when trying to find answers to complex and multilevel issues such as that of differential outcomes. However, synthesising the individual findings allowed us to interpret and propose a number of overarching themes as explanations.

The interviews reveal some clear overarching themes around exclusion, including:

- lack of belonging;

- lack of confidence in their ability to succeed;

- identity shifting or identity work – related to the extent to which individuals see themselves as members of the legal profession.

The survey data evidence the influence of remaining persistence. Remaining persistence, referred to simply as 'persistence' in socio-cognitive career theory (SCCT) studies (Brown and Lent, 2019) is a socio-cognitive factor associated with differential outcomes through its interaction with other contributory factors.

The rest of the report is structured as follows:

- An overview of existing research on the topic, including comparisons with the Bar, other professions and earlier stages of education.

- Discussion of the empirical findings of the research, focusing on the causes of differential outcomes. The discussion also touches on issues with the terminology used and available data, as well as on successful initiatives to address the issue.

- Drawing on material from the empirical findings of the project, the report concludes by putting forward some potential expert-suggested and evidence-based interventions for further consideration by the stakeholders involved.

As the starting point of answering the research questions of the project, the research team undertook an SLR. This investigated what the academic and selected 'grey' (ie highly relevant practitioner-focused reports or articles, published by professional or public-sector bodies) literature contributes to our knowledge of differential outcomes in legal professional assessments.

Following a filtering process on the basis of inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Appendix methodology in the Workstream 1 report), the SLR analysed 215 articles from law and management and organisational studies academic literature and 43 practitioner-focused reports published since 2010. It included global data on education performance, as well as data on the profession, putting legal professional assessments into a wider context.

Its findings were grouped into four topics, which emerged from the review process as being relevant to the research question:

- Challenges of terminology (eg difficulties presented by varied terminology used; and that minority ethnic groups are often grouped together, obscuring potential important differences).

- Background context, including socioeconomic (eg education systems; income; language competence; and neighbourhood and family) and educational factors (eg curriculum design; relationships between staff and students; social, economic and cultural capital; and psychosocial and identity issues).

- Professional and employment contexts (eg perceptions of the legal profession; barriers to entry; overlooking impact of factors other than merit; continuing influence of social class, privilege and whiteness; and negative lived experiences).

- Interventions at education, professional or institutional levels.

These were complemented by six overarching themes in the literature, which cut across several of the broad topics above. The overarching themes brought together factors that can explain the disadvantages that minority ethnic individuals face in different contexts, and which contribute to differential outcomes. These were:

- Social and cognitive factors in education and career, including self-efficacy beliefs and outcome expectations.

- Implications of holding minority status, including experiences of rejection and discrimination.

- Implications of holding multiple marginalised identities (known as intersectionality).

- The normalisation and privilege of whiteness and maleness/masculinity in dominant culture, as well as practices that indicate low representation, low participation and disadvantage for individuals who do not have these characteristics.

- The need for minority ethnic individuals to employ coping strategies to manage their marginalised identities, meaning putting extra effort to achieve positive outcomes in academic and professional settings.

- Lack of integration and unsupportive climates for marginalised identities in academic and professional settings.

The SLR findings confirmed that differential outcomes start early, many years prior to sitting any legal professional assessments. They also pointed to potential contributory factors that exist in professional contexts other than law. Drawing on that, and to provide some added context and showcase the reach of the problem, we looked at various sources of data covering the following:

- Educational outcomes at different stages of schooling using data from the Department for Education (DfE), Universities UK (UUK) and the Office for Students (OfS).

- Bar Standards Board (BSB) reporting on barristers' professional assessments.

- Other professions with assessments for qualifications.

Early years to university education data

Statistics from the DfE show differential outcomes on the basis of ethnicity, although these vary between levels of education, as shown in Figure 2. For example, using the benchmark measures described below:

- Chinese pupils consistently demonstrate the highest levels of achievement out of all ethnic groups at each key stage of schooling, from early years all the way to A-Level.

- Mixed ethnicity and white pupils' achievement very closely mirror that of the national average. Both groups demonstrate above average achievement up to Key Stage 1 (KS1). Mixed ethnicity pupils do better than white pupils at Key Stage 2 (KS2) and GCSE level. Both groups perform about the same at A-Level.

- Asian pupils demonstrated above average achievement at KS1, KS2, and GCSE level, but below average achievement at A-Level, including below that of Mixed ethnicity or white pupils (except for Indian pupils, who performed above average at A-Level).

- Black pupils' achievement is not noticeably lower than other groups to begin with. In fact, it is higher than average at KS2, but drops below average at GCSE level and then plummets to the lowest level out of all other groups by quite a margin at A-Level.

Figure 2: Percentage of pupils at state-funded schools achieving benchmark grades up to A-Level, by ethnic group (academic years vary, see 'Sources' below).

Note. *=Gypsy/Irish Traveller communities excluded due to small sample size.

Sources:

- Early years' (EY) data relevant for school year 2018/19. Source: Department for Education, 2020, Early years foundation stage profile results: 2018 to 2019

- Key Stage 1 (KS1) data relevant for school year 2021/22. Source: Department for Education, 2023, Key stage 1 and phonics screening check attainment

- Key Stage 2 (KS2) data relevant for school year 2021/22. Source: Department for Education, 2023, School results for 10 to 11 year olds

- GCSE data relevant for school year 200/21.Source: Department for Education, 2024, Key stage 4 performance

- A-Level data relevant for school year 2020/21. Source: Department for Education, 2023, Students getting 3 A grades or better at A level

Benchmark measures used by the above sources:

- EY: Percentage of 4- to 5-year-olds who met the 'expected standard' of development in reception year.

- KS1: Percentage of 5- to 7-year-olds at state-funded schools in England who met the 'expected standard' in phonics, science, reading, writing, and arithmetic.

- KS2: Percentage of 10- to 11-year-olds at state-funded schools in England who met the 'expected standard' in reading, writing, arithmetic, and GPS (Grammar, Punctuation, and Spelling).

- GCSE: Percentage of pupils at state-funded schools in England who got a grade 5 or above in both GCSE English and Maths.

- A-Level: Percentage of pupils aged 16 to 18 in England getting at least 3 A grades at A-Level.

The transition to and experience of A-Levels seems to be somewhat distinct from earlier stages given the discrete outcomes. However, it is worth noting that the data in Figure 2 are based on alternative methodologies for awarding A-Levels and GCSEs due to the impact of the Covid pandemic (ie teacher assessed grades). This is a period understood to have 'grade inflation'.

Differential outcomes for minority ethnic groups are further exacerbated at university, as shown in Table 1. Here fewer graduates from every minority ethnic group or subgroup (ranging from 60.4 percent for Black, to 69.6 percent for Asian and to 76.7 percent for Mixed ethnicity) achieved a First or upper second-class degree compared to their white peers (78.8 percent). This was particularly prominent for those that were awarded a First-class degree.

According to UUK and National Union of Students survey results, several key contributing factors may have a bearing influence on degree outcomes, namely:

- institutional culture;

- ethnic diversity among staff;

- inclusive curriculum content and design;

- sense of belonging;

- prior attainment;

- information, advice, and guidance;

- financial considerations;

- and preparedness for higher education.

Statistics (OfS, Higher Education Statistics Agency) also show how ethnicity intersects with other factors (eg gender, religion, domicile, SES, etc) contributing to differential outcomes.

Table 1: Percentage of UK domiciled undergraduates earning a First and upper-second class degree, by ethnic group, academic year 2021/22

| Ethnicity | 1st | 2.1 | Total share (%) | Group total | Cohort total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 34.30% | 44.50% | 78.80% | 197,760 | 251,150 |

| Black | 16.70% | 43.70% | 60.40% | 14,940 | 24,730 |

| Asian | 25.60% | 44% | 69.60% | 30,685 | 44,015 |

| Mixed | 30% | 46.70% | 76.70% | 11,850 | 15,455 |

Source: Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA), 2023, Table 26 - UK domiciled first degree qualifiers by classification of first degree, religious belief, sex, age group, disability marker and ethnicity marker 2014/15 to 2021/22

Legal professional education data

Moving on to the legal profession, a recent report by the BSB (July 2022) based on proprietary data, found ethnicity a highly significant predictor of performance on the Bar professional training course modules. This corroborated similar findings from an earlier BSB report (2019).

The authors found that, even when controlling for other variables, candidates from Asian, Black, Mixed ethnicity, or other minority ethnic backgrounds were all predicted to perform worse (ie have lower mean scores) than white candidates on the centralised assessments. These comprise the following three modules: Civil Litigation, Criminal Litigation, and Professional Ethics. Alongside ethnicity, other variables that were highly significant predictors of outcomes were prior attainment and UG institution attended, highlighting again the intersectional nature of potentially influential factors of differential outcomes.

Data from other professions confirm the existence of differential outcomes but also the issue's intersectional character. Although specific data on professional assessments from other professions were scarce, medicine was the sole exception, with a comparatively rich body of work on the topic. For example, the General Medical Council (GMC) reported on:

- the Membership of the Royal Colleges faculty exam data;

- the Annual Review of Competency Progression data from PG training bodies;

- recruitment outcomes of year two foundation trainees (F2) in specialty training.

It found lower pass rates in specialty exams for UK graduates of Black/Black British heritage (62 percent), Asian (68 percent) and mixed heritage trainees (74 percent) compared with their white peers (79 percent). It is not within the scope of this work to go into a detailed discussion of the research in medical professional assessments in this report, but it drew parallels with the findings from this research. The similarity of findings across medicine and law, can support calls (noted later) for stronger stakeholder cooperation and exchange of best practice to tackle differential outcomes in professional assessments.

Considering the SLR alongside the comparative data analysed, our findings helped identify gaps and informed the design and specifics of the empirical research in Workstream 2. Identified gaps included:

- lived experience of minority ethnic candidates of legal professional assessments;

- multilevel approaches to potential causes of differential outcomes;

- how any potential causes manifest themselves in legal professional assessments, including the influence of the legal profession.

In order to address the gaps in past research, described above, both qualitative and quantitative empirical work was undertaken. For instance, the aim was to take into account the lived experience of minority ethnic individuals, and thus enable improvements to be made. The combination of both qualitative and quantitative methodologies meant that our insights on the issue of differential outcomes by ethnicity have both generalisability and depth, enabling us to evaluate how potentially influential factors may work together to impact outcomes.

Our qualitative empirical work involved a total of 59 semi structured interviews with:

- Minority ethnic individuals who had recently undertaken, were preparing for or were planning to pursue PG professional courses to qualify as solicitors (18 'Candidates').

- Educators involved with legal education at the UG, PG, or preparatory courses for legal qualifications level (20 'Educators'). This group is a mix of majority and minority ethnicity.

- Individuals holding senior positions within law firms or working in close partnership with them (21 'Seniors'). This group is a mix of majority and minority ethnicity.

The quantitative empirical work involved survey responses from aspiring solicitors from any ethnicity, in particular:

- 700 UG law students (the 'UG sample') planning to qualify as solicitors;

- 510 Candidates on an LPC course (the 'LPC sample') during the calendar year of 2023. A subset of 160 participants also provided their final LPC grade after completion of the LPC (others had not completed the LPC by the relevant time or chose not to provide us with their final grades).

Despite the limitations of our sample as set out below, there were differential outcomes in both the UG and LPC samples, including those collected at a later point in relation to their final LPC results. Although not always statistically significant (something that could be attributed to the size limitations of the sample), the fact we do see differential outcomes is key to the validity of our sample and results.

Below, we combine the discussion of these two empirical strands of work that formed part of Workstream 2 of the project. Full details of the findings and more details on the participants/sample from each empirical piece can be found in the Qualitative Interview Insights Report and the Quantitative Data Insights Report.

Challenges with terminology and data

Before delving into the discussion of the causes as they emerged from the empirical part of the research, it is worth touching briefly on challenges of terminology and data collection. There were challenges in:

- framing the factors underlying the differential outcomes;

- available data;

- collecting, and drawing conclusions, from our own data.

The findings described in this report should be interpreted in light of these challenges and limitations, which may also serve as the basis for future work in this area.

Problematic terminology and categorisation

The SLR and our interviews highlighted issues with categorisation when examining differential outcomes. The SLR showed that work tends to focus on a binary distinction between one of the minority ethnicities and the white majority ethnicity, which can overlook experiences of individuals from other minority ethnic groups (see Workstream 1 report, section 2.1).

Similarly, in the interviews, the Candidates and Educators contested the use of the term 'Black and minority ethnic' as being too broad to be useful, risking oversimplifying the issue. They also highlighted the inconsistencies that lead to classifications on the basis of skin colour for some, and on the basis of their and/or their families' country or subcontinent of origin for others. These are perceived as problematic by students. Similar concerns were raised in a GMC Report (2018). Relatedly, the categorisation of subgroups, whose experiences may differ, into broad ethnic groups (eg Black, Asian, white, Mixed and Other ethnicity) may prevent the identification of factors that are important for particular groups.

Our interview data also highlighted problems with terminology, specifically in terms of the use of the term 'attainment gap' which is commonly used to refer to differential outcomes, especially in the UK. Some of the Educators and Seniors we interviewed were not comfortable using the term, as they felt that it individualises what they saw as a systemic problem. A suggested alternative term that was perceived by some as better capturing the complexity of the problem was 'awarding gap', which is common in the US literature. It was also noted how terminology that avoids the use of the term 'gap' altogether might be more effective in communications with students. We therefore decided to use the term 'differential outcomes'.

Limitations in publicly available data

Compared to other professions, the better availability of data on performance in legal professional assessments by ethnicity and other protected characteristics is welcome. However, our interview data revealed that there were still some criticisms in relation to the data that are available. There were calls from both Educators and Seniors to further disaggregate minority ethnic outcomes in legal qualifications data. More precisely, they called for disaggregated data:

- between and within ethnic groups;

- on those internationally or UK-educated at school level;

- on type of UK school;

- on those for whom English is a second language.

Each of these aspects was believed to have differing potential impacts on outcomes and aggregating data into one group was not seen as meaningful.

Some Educators and Seniors raised the issue that small sample sizes within organisations are often given as a reason for a lack of disaggregated data. Their response was that this should not be an 'an excuse to ignore the issue' but that institutions or organisations should seek more data from interviews or focus groups. Regarding the LPC, it was also suggested that it is important to look at differential outcomes between the different providers.

Overall, being nuanced about the specifics of the group that is being examined is essential, in order to avoid blanket assumptions about minority ethnic students and their circumstances. Better and more nuanced data would also help inform interventions to address the issues.

Limitations of empirical data generated in this project

Both our interview and survey work had limitations that should be considered in interpreting the data. Full consideration of the limitations of each stream of empirical work is provided in the separate reports.

One important limitation to note is that participants in both of our empirical methods are not necessarily representative of all participants who sit the LPC. This reality was particularly evident in participants reporting their LPC results. Comparing those data to LPC data held by the SRA (from the academic sessions of 2013 to 2014 and from 2015 to 2021) suggests that our sample did not have proper representation of participants who were relatively low achieving on the LPC. Moreover, we did not interview any Candidates who had failed the LPC.

There were also limitations from the relatively small survey sample size, compared to the overall numbers in UG and professional legal courses. This means that our raw findings should be read in conjunction with the available figures for the performance of the totality of the student population.

Finally, it is worth noting that in the survey findings below we report only those that reached the conventional academic threshold for statistical significance (p < 0.05). That is, we only report the findings where the likelihood is 95% or higher that the difference observed is not just a result of chance.

We also attempted to confront issues around categorisation in our survey work by collecting information on participants' own definitions of their ethnicity, which resulted in having up to 20 different ethnicities in the data. However, due to the low sample size of the survey data, for analysis participants had to be grouped under the commonly used broad categories of:

- White (English, Welsh, Scottish, Northern Irish or British, Irish and any other white background);

- Mixed ethnicity (white and Black Caribbean, white and Black, white and Asian and any other Mixed or multiple background);

- Asian (Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Chinese and any other Asian background);

- Black (Caribbean, African background and any other Black, Black British or Caribbean background);

- Other ethnicity (Arab and any other ethnic group).

These broad category groupings were pragmatic for statistical analysis but are extremely problematic in terms of understanding the differences that may exist within the groupings. By extension, this is also problematic for understanding the causes of the differential outcomes for specific ethnic groups. This is partly addressed by our use of interviews, which provided rich data about specific experiences. Future work could try to further isolate experiences of specific ethnic subgroups where possible, recognising that the complex factors underlying differential outcomes may differ for different groups.

Causes

Four key causal explanations underlying differential outcomes emerged from our research. The first three represent causes linked to clear time periods or contexts relevant to the research question. The fourth includes overarching factors explaining differential outcomes that cut across these periods/contexts and reflect the intersectional dimensions of differential outcomes by ethnicity.

The collected data reveal the complexity of the issues. Therefore, there is a need to take a socio-cognitive (two-way interactions between the individual and their social environment), multilevel and lifecycle approach to understanding differential outcomes. Such an approach is also intended to avoid the pitfall of falling back on more 'acceptable' explanations for differential outcomes (such as poor schooling), rather than addressing harder issues. The latter include privilege or the 'myth of meritocracy' (described in the SLR report) present within legal education and/or the profession, or other issues related to the support, administration and/or regulation of legal professional assessments.

Background context: Family background, SES and schooling

Environmental circumstances, and particularly family background, schooling, and socioeconomic status (SES) manifest themselves in every context of students' and candidates' lives. These feed into their human, social, cultural and financial capitals, ie the range of resources available to them.

The SLR showed there is a series of environmental factors that may have an impact on differential outcomes, such as:

- parental income;

- parental education and class background;

- parental language proficiency;

- geographical location;

- neighbourhood poverty;

- family priorities;

- a country's economic context;

- macro educational policies.

Our SLR findings also noted, however, that research often focuses on one or two of these factors, rather than taking an intersectional or multilevel approach. Academically, such approaches are more complex and likely to lead to less clarity in findings but are more likely to present a more holistic understanding of such complex issues.

Overall, our interviews and survey data explored most of the background factors listed above from the SLR (except for a country's economic context and macro educational policies). These confirmed some key differences in background context based on ethnicity that have the potential to feed through into differential outcomes.

Drawing on data from our interviews, Candidates growing up in the UK tended to experience early and school-level differences based on their ethnicity. Often, they became more aware of SES and family background differences later, particularly as they transitioned away from their local environments. Educators touched on most of the environmental circumstances that came up in the SLR and explained how ethnicity and family background intersect to influence school-level outcomes. Seniors tended to focus on the impact of type of school attended, seemingly conflating ethnicity and class. Both groups assumed environmental circumstances to be causal factors of differential outcomes. And Candidates and Educators singled out family support, the school and teacher input, and how the schooling is experienced by minority ethnic individuals as important standalone influential factors.

Our survey data also highlighted potential disadvantages relating to some background factors for minority ethnic participants, described below. For instance, the UG and LPC samples demonstrated lower levels of contextual support (ie financial and familial support for their legal education) in minority ethnic participants. However, there were several variables where expected differences were not observed, perhaps due to a lack of representativeness in our samples, discussed above. In addition, findings were inconsistent between the two samples. That is, other predicted differences which might adversely impact further and higher (tertiary) education (eg lower English proficiency, lower social connectedness in early education, lower parental involvement) were only demonstrated in the LPC sample. In this sample, there was a more pronounced negative background context for Asian participants than in other minority groups.

Family background and support

In terms of family support, the survey data suggest that compared to white LPC participants, Asian participants had lower parental involvement (ie lower perceptions of the interest and engagement of their parents in their academic activities during early schooling). This may be linked to English proficiency, as Asian compared to white LPC participants' parents had lower English proficiency. Educators also pointed to this, for example, without English proficiency, a parent may not be able to engage with and help a child with homework.

At later stages in schooling, survey data suggested that Asian and Black compared to white LPC participants reported having less contextual support. This indicates less assistance and encouragement from family and friends, for example, received in their decision to pursue a legal education and career. However, Candidate interview data presented a mixed picture on this. Some Candidates (particularly with an international background) felt very supported in, and even positively pushed towards, their decision to study law. Others distinguished between emotional support or encouragement, and practical support in terms of managing the process to university.

SES background

SES is a factor frequently mentioned in research regarding educational outcomes, as seen in the SLR. It was also often brought up during our interviews. In our survey we asked whether the participant had received free meals during their school education and to self-report on their social class, which is subjective. Responses in these questions of the survey were inconclusive; they either were affected by constraints related to the small sample size or were not in accordance with predictions.

The inconclusive responses in self-reporting may point to the unrepresentativeness of our sample and may not apply to the broader population. They may also call into question the reliability of self-reported measures of social class. However, previous research would suggest subjective social class is a reliable predictor of outcomes because in many ways one's subjective perception fundamentally impacts perceptions, behaviours, stress levels, and so on. Accordingly, this may explain why our minority ethnic LPC sample performed well in their legal professional assessments.

School experiences

During our interviews, it was viewed that schooling itself often placed minority ethnic students at a disadvantage at the start of university. More specifically, Educator and Senior interviewees highlighted that schooling, including the type of school attended, or even its location, could influence a range of social and cultural skills which increase the likelihood of performing better in legal professional assessments. This also feeds into candidates' confidence, which links to some of the overarching factors discussed later (eg self-esteem and remaining persistence). Some of the Candidates that were interviewed corroborated this by reflecting how negative experiences from early education may influence their behaviour and interactions at later stages of their education and beyond.

The survey asked participants about their focus on academic learning, their academic motivation, and their social connectedness (ie sense of belonging and positive relationships) in school, to elicit information about their early education experience (ie their education experience prior to entering university). These may feed into each other; for example, if a child feels less connected in school, this may impact on their 'academic motivation'. Academic motivation is a concept usually referring to pre-university education experiences, that is: 'students' general interest, engagement, and enjoyment in learning and school' (Anderson-Butcher et al., 2012, p. 187).

In our survey, Black LPC Candidates compared to white LPC Candidates had lower levels of academic motivation, as well as of 'academic press' in pre-university education, (a concept that refers to 'normative emphasis on academic success and conformity to specific standards of achievement'; Lee & Smith, 1999, p. 912). Moreover, all minority ethnic LPC Candidates compared to white LPC Candidates had lower levels of academic motivation in early education, which, as we explain below, is affected by their education experiences.

Finally, Black and Mixed ethnicity LPC Candidates had lower social connectedness ratings compared to white LPC candidates. Our interviewees stressed that the above factors should be taken into account as part of an intersectional approach to the issue. And they are all related, as our SLR found that the social interactions between teachers, students and peers are critical to successful learning.

It is worth repeating that this study identifies lower levels of academic motivation and/or academic press among specific ethnicities, but these factors do not imply that ethnicity is a determinant of academic motivation and academic press. This is because these factors are affected by external events and interactions, including teachers' expectations and behaviour, and experiences of discrimination from peers.

Simply put, there are unique intersections of challenges that feed into later stages of one's education and beginning of professional life. These would inevitably vary from one minority ethnic candidate to the next. Altogether, however, these findings show marked disadvantages for minority ethnic participants in terms of important factors in early education (ie lower levels of academic press, academic motivation and social connectedness). This finding suggests that they may have more challenges leading into tertiary and then professional education.

Legal education context

Legal education has naturally been identified as an important context in which a range of potentially influential factors arises (eg learning experiences, representation, institutional support, interactions with teaching staff and colleagues, fit, discrimination, etc). The empirical data identified these factors at all levels and types of legal education, be it at UG or PG level, and regarding academic or professional assessments.

Although it is acknowledged that a significant percentage of candidates in legal professional assessments do not have a UG degree in law, the remit of the research could not be expanded to empirically examine the UG experience in other disciplines. The discussion below only distinguishes the level or context when relevant.

Entry

The influence of background factors mentioned in the previous section means that students enter university with skills and knowledge disparities, including in law courses. For example, differential outcomes in A-Levels, coupled with inaccurate A-Level predictions, can impact entry to university. Performance in these also impacts recruitment by law firms, including for schemes that financially cover preparatory courses for legal professional assessments alongside financial maintenance.

Similarly, factors prevalent during and prior to UG studies can have a knock-on impact on the professional course level. According to our survey data, Black LPC Candidates had significantly lower UG degree outcomes compared to their white peers. This indicates that Black LPC Candidates have entered the preparatory stage for legal professional assessments as lower-achieving students compared to their white counterparts.

Support

All Educator interviewees expressed concerns about how students from lower entry or nontraditional routes and backgrounds ('traditional' having been described as white, middle-class and privately educated) were supported at university. Indeed, AdvanceHE data show how minority ethnic students are far less likely to get an upper second-class or First-class degree compared to their white peers, even when they enter with the same A-Levels (2019). Despite the hive of activity and support that most universities now claim is available, Educators were clear that there is a difference between making support available and creating an environment where those who need it feel confident to access the relevant support.

The increase in student numbers studying law ('massified' legal education) has led some of the Educators we interviewed to note how they no longer have the time or resources to support all those falling behind. They also observed that, for minority ethnic students, the positive impact of additional support often does not materialise until later in the degree course, by which point training contracts or other law firm opportunities have passed them by. Seniors from nontraditional backgrounds expressed opinions doubting that minority ethnic students could be successful in today's massified legal education environment, given the lack of individualised support and potential debt incurred to study law.